Nicole~

The Birds by Tarjei Vesaas

'We're coming, we're coming,' somebody said. ' You're ready, aren't you?'

Vesaas's poetic words, as they flit and float within the currents of Mattis's uncomplicated mind, as he struggles to articulate them meaningfully, have proven that beauty of nature, nature's beings and the nature of one's being might simply be understood, less from the spoken word, if one would stop to quietly listen. Mattis, who exists naturally, with the emptiness many take several life cycles to achieve, is Vesaas's example of this.

I HAVE NOTHING to add to the glowing reviews of this novel ( present on that other review site) , that would not be insufficient or superfluous, but for this treasure found in the poem by the same name, inspired by this novel and written by Tarjei's wife, Halldis Moren Vesaas.

The Birds

All day long I listened

to the rushing wings over my head.

High in the sun-blue air

a flock of birds flew their unburdened flight.

Today I thought once

that one of them was sinking down

as if wanting to be my guest.

I thought I heard a pair of wings

standing out among the others

rowing hastily toward me.

Thus among all of them

was a bird that was mine and I opened

every door, every window in my home.

Perhaps it was only a small, grey bird,

but with bright eyes and warm, soft feathers

and driven by impatience

toward the heart that waited just for him,

as a dry river bed

waits to be flooded.

...

Closer, closer the sound of wings,

like a beating heart

- stopping suddenly; was the bird

standing still on my roof?

Then the fresh sounds, as if the heart

started to beat again,

but faster now and fainter

and further and further away

until it swings around anew:

the rush of thousand beating wings.

I know now that the bird will

not roost with me today.

...

Dusk falls. High in the sun-red air

the passage of birds as before.

Down here the shadows have taken my house.

It still is waiting with open windows

and open door.

My feet are heavy and tied to the earth.

Soon I can no longer glimpse the birds

that freely roam the air.

But now when they swing around again

they burst out in song

so that the evening sun glows warmer.

Who are you who dared to call

one of these birds your own...

Cited in The North American Review, Vol. 257, No.1 (Spring, 1972), p.59

Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

In Americanah, the two main characters are modern-day Nigerians: Ifemelu and her (one true) love, Obinze. Middle-class and educated, they have decided to migrate abroad, not for reasons of political conflict or poverty, but for the lack of foresight of their country's progressiveness, "the oppressive lethargy of choicelessness." Futures are brighter, success quicker in the other countries. Obinze immigrates to Britain, Infemelu to the US. In the novel, race and differential social conventions between the three countries are examined, weaving in the love story of Ifemelu and Obinze over the course of two decades.

Adichie's characters as immigrants experience various levels of inequality and road-blocks, hindered not only by the stereotypical culture and race differences, but the inability to effectively resolve them. Obinze struggles with the usual escalating illegal trappings of the undocumented immigrant; for my own preference, I'll just focus on the main character, Infemelu, from here on.

Adichie's novel is as much about race perceptions in the West, as it is about the disparateness within and between races, measured to be as distant as the two continents. The story primarily follows the life of Ifemelu, as a Nigerian woman whose journey to America dims her dreams and dissolves her identity. Infemelu discovers that racism, as she experiences it, is multi-dimensional: White-race/Black-race; American-Black/ Non-American-Black; White-woman/Black-woman.

I did not think of myself as black, I only became black when I came to America.

Infemelu is sharply awakened to the reality that in America, her "blackness" is not invisible, it goes noticed and is reacted to, no matter who you are or where you're from. She realizes that survival in America requires her to climb the 'racial hierarchy', assimilate, change her image: her hair, manner of speech, her accent, her way of dress. Ifemelu's pursuit of the immigrant dream follows a crooked path with many challenges and pitfalls for a Non-American Black woman; nonetheless, she finds her voice in blogging: a thing that is as natural to her as her kinky roots.

To My Fellow Non-American Blacks: In America You Are Black, Baby

Dear Non-American Black, when you make the choice to come to America, you become black. Stop arguing. Stop saying I'm Jamaican or I'm Ghanaian. America doesn't care. So what if you weren't "black" in your own country? You're in America now...So you're black, baby. And here's the deal with becoming black: You must show that you are offended when such words as "watermelon" or "tar baby" are used in jokes, even if you don't know what the hell is being talked about- and since you are a Non-American Black, the chances are that you don't know.

Racism didn't change too much for Infemelu over many years; it only further obscured the immigrant dream. Ifemelu's journey to the West eventually turns full circle to where her natural roots sprang, but returning with her is the rediscovery of her authenticity - a theme that basically drives Adichie's female protagonists- to be free of coercion and artificiality, to hold fast to her independence, the oneness of being woman, intelligent, black and beautiful - inside and out, roots and all.

Americanah, although bogged down at times with strained rhetoric, holds the reader's attention with well- balanced shifting themes and geographic hopping, with Adichie's keen observations and humor, making this quite hefty work when generously paced, a delightful if not provocative read.

Notes of a Native Son by James Baldwin

To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious, is to be in a rage almost all the time. So that the first problem is how to control that rage so that it won't destroy you. - James Baldwin from "The Negro in American Culture", Cross Currents, XI (1961), p. 205

In his dramatic and provocative short piece Notes of a Native Son (1955) included in the ten essay volume of the same title, Baldwin connects a series of coincidental events, unifying them in a brilliantly conceived aesthetic design. Segmented in three parts, he reviews: an act of rage against a waitress in a restaurant; his father's death and his sister's birth; a race riot in Harlem, his father's burial and his 19th birthday.

I

In order really to hate white people one has to block so much out of the mind – and the heart – that this hatred becomes an exhaustive and self destructive pose.

Baldwin examined parallels between his younger, unenlightened self and his father's characteristic of garnering the enmity of many with his often unchecked fury. In late June of 1943, an experience of discrimination in a restaurant ignited Baldwin's already building rage, leading him to throw a water pitcher at a waitress. Suddenly frightened by what he had done, he fled the scene, later speculating: "I could not get over two facts, both equally difficult for the imagination to grasp, and one was that I could have been murdered. But the other was that I had been ready to commit murder. I saw nothing very clearly but I did see this: that my life, my real life was in danger, and not from anything other people might do but from the hatred I carried in my own heart."

II

I imagine that one of the reasons people cling to their hates so stubbornly is because they sense, once hate is gone, that they will be forced to deal with pain.

July 29th, 1943 : The coincidence of his sister's birth, the same day as the death of his father - a man who was, to Baldwin, "certainly the most bitter man I have ever met," whom he considered was poisoned by the intense loathing, fear and cruelty he carried in him (diagnosed with mental-illness and later tuberculosis) - symbolically shaped in Baldwin's mind the death of an old toxic bitterness and the forming of an untainted, new beginning, to forgive and accept..."life and death so close together, and love and hatred, and right and wrong...." Ironically, his father's simple words echoed with posthumous meaning, that "bitterness is folly."

III

Harlem had needed something to smash. To smash something is the ghetto's chronic need.

August 3rd, 1943 : As if "God himself had devised [ it ] ", the day that marked his 19th birthday, the day his father was returned to the earth, a race riot roiled in Harlem. Ghetto members vented their anger, fought one other, destroyed and looted in "directionless, hopeless bitterness", leaving smashed glass and rubble as 'spoils' of injustice, anarchy, discontent and hatred. These events deeply affected Baldwin who upon reflection sought a change from ill-will to good, to let go the demons and darkness that threatened to consume him - the hatred, bitterness, rage, violence, disillusionment, the social problems perpetuated by "being Negro in America."

It was necessary to hold on to the things that mattered. The dead man mattered, the new life mattered; blackness and whiteness did not matter; to believe that they did was to acquiesce in one's own destruction. Hatred, which could destroy so much, never failed to destroy the man who hated and this was an immutable law.

As a writer, Baldwin depended greatly on his past experiences, grasping at every bittersweet drop. "I think that the past is all that makes the present coherent, and further that the past will remain horrible for exactly as long as we refuse to assess it honestly." Whether by coincidence or divine making, Baldwin's reflection on those fateful few days was spiritual, cleansing, revelatory, life-saving. From it germinated a new philosophy and idealism that lingered strongly and eternally, nourishing a poetic power and sustaining a literary genius for many years hence.

Fire from 'A Journal of Love' (1934-1938) by Anaïs Nin

...following one's instincts alone is human, that faithfulness in love is unnatural, that morality is man-made ideology, that self-denial, which is necessary to be good, is denial of the bad natural self out of self-protection, and thus the most selfish thing of all.

Anaïs Nin (1903-1977) began her diaries at age 11 years old as a personal letter to the father who deserted her, her mother and brother. It became a necessary part of her existence, written with melodic lyricism of sex and love. Worked and reworked into a hefty fifty year record, it took the shape of a hybridized art form, serving as a confessional and confidante, a scribbler's notebook, an extremely candid autobiography, a self-research project, and to those who knew her personally, a literary monument interspersed with fiction; leaving many critics to call it a 'journal-novel.'

Fire flows like a continuous intimate moment focused on the many facets of love, covering Nin's multiple romantic relationships from Hugh Guiler (her husband), simultaneous liaisons with Gonzalo Moré and Dr. Otto Rank (her psychoanalyst) to name a few, to the long standing, complex affair with Henry Miller. Set between Europe and America, Nin paraded alternately as friend, paramour, muse, seductress, artist, woman; duplicitous, illusive shape-shifter.

The entries stand as an authentic, reflective self-exploration, an unrepressed, uninhibited, immodest record of her life, without artifice or shame or apology. Nin habitually wrote as soon as events happened to preserve their emotional power. She faced her writing with the obsessiveness and desperation of an addict needing her 'opium' . Without it, she felt neither real nor original nor alive.

Intimate thoughts and emotions pulsate through her pen organically, passionately, sensually, frenzied. More than mere scribblings of unregulated emotions, Nin self-analyzes with insight deep and incisive, of a degree less from an intuitive or sharpened sense of perception than a honed, disciplined psychoanalytic understanding of human behavior.

Gonzalo is a sensual volcano, afire, never enough. I am ready to ask for mercy! I did not believe, after all the idealism, the chastity, the emotionalism, that we could descend into this furnace of animal desire. Now it is several times in one moment, until we lie dead with exhaustion. He smears his face with honey and sperm, we kiss in this odor and wetness, and we possess each other over and over again madly. Yet I cannot have an orgasm. Why, why, why?

Fire, a small but flammable portion of what must be a complex, multi-layered set of journals, is as fascinating as a novel compact with sensational characters all portrayed in vibrant colors. Crafted by the tool of a skilled artist - as a woman with the beauty of Venus and the sensual power of the feminine mystique; as a writer with the elegant hand for sultry, poetic prose and a touch of the surreal; as an unbound dabbler in the unconventional and an astute analyzer of it - it is obvious that Nin's greatest creation is herself.

I live in a sort of furnace of affections, loves, desires, inventions, creations, activities, and reveries. I cannot describe my life in facts because the ecstasy does not lie in the facts, in what happens or what I do, but in what is aroused in me and what is created out of all this... I live in a very physical and metaphysical reality all together...

Fire clearly represents the feverish push toward Nin's most ardent desire; the neurotic, breathless, unbridled motion toward satisfaction, the climactic discovery, that is to say - the ultimate knowing and understanding of herself.

This is the story of my incendiary neurosis! I only believe in fire. Life. Fire. Being myself on fire I set others on fire. Never death. Fire and life. Le jeux.

Portraits of a Marriage by Sándor Márai

Sándor Márai began his literary career as a poet whose artistry is well suited for this novel of a marriage viewed from the three corners of a love triangle. Márai deftly manipulates his reader through the novel's intense narrative, allowing his three main characters to perform their passionate monologues, each a moving tale as distinct and contrasting as their differing social backgrounds.

The story opens in a bar in post-war Budapest with Ilonka, who comes from a middle class family, holds marriage as sacrosanct, and divorce a sacrilege; recalling her marriage to Peter, an aristocrat, with loneliness and bitter regret. "I understood that my husband whom I had previously believed to be entirely mine - every last inch of him, as they say, right down to the recesses of his soul - was not at all mine but a stranger with secrets." Her rendition of marital disillusionment, disappointment, and the betrayal that drove them to divorce is touching and sensitive.

Peter's perspective follows, formed by a highly privileged upbringing, therefore more cerebral than emotional; adding the necessary detail that sheds some light on the relationship that baffled the innocent Ilonka. "A man's life depends on the state of his soul.... Your heart must let me go. I can't live under conditions of such emotional tension. There are men more feminine than me, for whom it is vital to be loved. There are others who, even at the best of times, can only just about tolerate the feeling of being loved. I am that kind." Peter later matured in his thinking but remained cynical. He was not my favorite character.

The most striking voice comes from Judit, the second wife, whose dirt-poor rags to riches story gives the reader a clear vision of the change also occurring in Hungary. Her version is the most earthbound and realistic, her own change the most dramatic. "The whole business of the bourgeois and the class war was different from what we proles were told. These people were sure they had a role in the world; I don't mean just in business, copying those people who had had great power when they themselves had little power. What they believed was that when it came down to it, they were putting the world into some sort of order, that with them in charge, the lords of the world would not be such great lords as they had been and the proles would not remain in abject poverty, as we once were. They thought the whole world would eventually accept their values; that even while one group moved down and another one up, they, the bourgeois, would keep their position - even in a world where everything was being turned upside down."

On the surface, Márai created a soulful, deeply intimate story built on themes of love, marital disillusionment, jealousy, social class, even death. Since much of the flashback events occurred in wartime, the book is not only a journal of the deconstruction of a marriage, it chronicles the decline and dissolution of a strictly hierarchical society, and the barbaric destruction and widespread devastation that left Europe in ruins as a result of the war. The ill-fated marriage and Europe might serve as metaphors, leaving one in no doubt of Márai's genius in weaving this historical and psychological work of art.

From the back matter-

A Note about the Author:

Sándor Márai was born in Kassa in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in 1900, and died in San Diego, California, in 1989. He rose to fame as one of the leading literary novelists in Hungary in the 1930s. Profoundly anti-fascist he survived the war but persecution by the Communists drove him from the country in 1948, first to Italy, then to the United States. His [highly acclaimed] novel Embers was published for the first time in English in 2001.

*************

Quotable quote:

“Do you also believe that what gives our lives their meaning is the passion that suddenly invades us heart, soul, and body, and burns in us forever, no matter what else happens in our lives? And that if we have experienced this much, then perhaps we haven’t lived in vain? Is passion so deep and terrible and magnificent and inhuman? Is it indeed about desiring any one person, or is it about desiring desire itself? That is the question. Or perhaps, is it indeed about desiring a particular person, a single, mysterious other, once and for always, no matter whether that person is good or bad, and the intensity of our feelings bears no relation to that individual’s qualities or behavior?”

― Sándor Márai, Embers

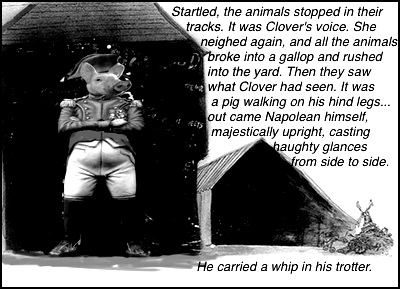

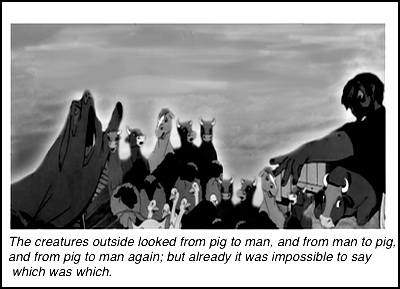

George Orwell's

Once upon a time on a farm, animals revolted against the unfair treatment they suffered at the hands of humans. They shouted in the fields: "Man serves the interests of no creature except himself. And among us animals let there be perfect unity, perfect comradeship in the struggle. All men are enemies. All animals are comrades." And so, a new order formed - initially with good intent - and all the animals, even the illiterate ones, agreed to abide by its newly written commandments:

Then one terrible day, a disease sickened some of the animals, threatening their utopian life - a viral attack that plunged the farm into counter-revolution. It was the pigs..the pigs sought to lead the new society, corrupting into a powerful, self-serving party!

And so it came to pass that the once fair and bright future of Animal Farm dissolved into one of despair and pessimism, as the realization that although all animals were equal,some animals were more equal than others, and that the more things changed, the more they stayed the same.

Children would enjoy this Aesopian tale for the entertaining notion of animals with human characteristics such a speech and walking on two legs. For the adult reader, apart from Orwell's strong views on Socialism, this fable represents dystopia for man: that even in his desire for an ideal egalitarian way of life, he will undoubtedly return to a power hungry, hierarchical system - one that neither beast nor man can escape.

Animal Farm was published in 1945 and interpreted as George Orwell's political satire against Stalinism in the USSR; its subtitle A Fairy Story pointed to the "Soviet myth" that the West popularly believed to be Stalin's socialism, which Orwell sought to debunk as more accurately Stalin's totalitarian dictatorship. Orwell's parody of Socialist ideals corrupted by the Soviet regime showed that revolution could often lead to the substitution of one tyranny for another.

The best of ideals corrupt when divorced from humanity.

The Son by Jo Neabø

Jo Nesbø is a pure gold phenomenon. An economist, active musician/songwriter/vocalist, ex-footballer (retired due to injury); he confessed in 2013 to be behind the pen-name of Tom Johansen; novelist of a successful children's book series featuring Fart Powders and a wildly popular, mad-cap Doctor Proctor; he's considered the top Norwegian crime fiction author globally, and now with his new anti-hero, there is five-star splendor in The Son...

30 year old Sonny Lofthus is kept in a perpetual catatonic state through a constant supply of drugs. Left in a position to be easily set up for the crimes of others, he is imprisoned at Oslo's most modern state of the art institution, Staten - an impenetrable structure that itself oozes evil from every brick of its foundation. Lofthus's name is even more tainted by the fact that his father committed suicide, a disgraced officer gone astray by his own corrupt misdeeds.

There is a power struggle of good and evil in Nesbo's uberdark novel. I'm not just talking 'good guy- bad guy stuff', or even a seasoned crime hero with a looming shadow like Harry Hole. The difference in Sonny Lofthus's case is that, although 30 years old, he has the mind of a teenager, an untested innocence, has been in prison nearly half his life and is already in the fires of hell. Immediately the reader sympathizes with his character. Immediately, we know that any ill conceived actions he does next will be tolerated, because we want him to prevail.

Counterbalancing this black soul is an aura of mystification - Sonny appears to have the touch of a miracle-worker: he can see into the deepest of a man's soul, he can absolve the worst of sins weighing on the guilty conscience, he can heal the sick, well, maybe spiritually anyway. And he's highly intelligent, too. Maybe he is the almighty?

When Sonny learns from an inmate that his father was set up and was, in reality, murdered, he plans his escape in the clever, high-tech fashion that only Jo Nesbo could pull off, nothing would get in the way of the bloody string of vendettas he has in mind. Nesbo readers expect the mind bending plot twists and palpitating thrills, the highly sophisticated criminal systems and Norwegian underworld network, they're here. New are the half-way hostels: the public funded programs that provide sanctuary for drug addicts to get off the streets of Oslo. This is such an interesting concept, one I would love to see compared to the ridiculously over-priced drug rehabs in this country.

There's a lot to entertain the die-hard Nordic noir reader; once finished, you'd want to read it again, straight away. I look forward to much more of Sonny Lofthus. I highly recommend this new Nesbo crime thriller (apparently to become a TV series).

We love Sonny, Jo!

Skoal!

Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

The world has to know the truth of what is happening because they simply cannot remain silent while we die. - Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Adichie's novel illuminates the reality and disintegration of Nigerian life in wartime during the 1960s. The Biafran war waged between 1967-70 was Nigeria's politically and ethnically charged battle of North vs South, specifically the southeastern region, where the unsuccessful fight for secession left 1 million civilians dead. Half of a yellow sun describes the Biafran flag; it symbolized the struggle of its people for independence and a brighter tomorrow.

Red was the blood of the siblings massacred in the North, black was for mourning them, green was for the prosperity Biafra would have, and, finally, the half of a yellow sun stood for the glorious future.

The novel features the daily lives of Igbo people of different social levels from the well educated and bourgeois to illiterate country peasants. Adichie's characters are strongly defined individuals whose personal lives and interrelationships go through fragmentation and change, their rise and fall in violent tandem with the country's horrific civil war.

There are some things that are so unforgivable that they make other things easily forgivable..

Although the story centers on the love-hate conflict between twin sisters Olanna and Kianene, moving from jealousy, betrayal, and distrust, the more compelling tale belonged to Ugwu - the good natured, loyal houseboy - who rose up through better education, but miserably fell when, conscripted in the army, his vicious regrettable action would leave him self-loathing, morally decayed and damaged forever.

This was the most visceral war novel I've read in a while, on a region not well known to me. Adichie's voice is powerful, genuine, resonant in the narrative of Biafra's painful victory and defeat; in the story of the resulting broken lives, and a country's blood -soaked odyssey.

For, while the tale of how we suffer, and how we are delighted, and how we may triumph is never new, it must always be heard. - James Baldwin

*************

I had no interest in writing a polemic. I was aware that the book would in the end reflect my world view--it would be a book concerned with the ordinary person, a book with unapologetic Biafran sympathies, but also a book that would absolutely refuse to romanticize the war. I wanted to avoid making Biafra a utopia -in -retrospect, which would have been disingenuous-- it would have sullied the memories of all those who died.

- African Authenticity" and the Biafran Experience by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie from Transition, No. 99 (2008)

Five Modern Nō Plays by Yukio Mishima

Nō for Dummies

First off, let me say that I started reading these plays nō-ing nothing about Kabuki or Nō theater, just that I have always admired Japanese dramatic arts even though I couldn't much understand it. It is like listening to Shakespeare for the first time, in high frequency.

A little research ( ok, very sparse research ) went a long way to assimilate to the subtle nuances of this medieval art form.

Nō, literally translated as "skill or ability" - the lyrical, traditional Japanese style of theater drama - draws its distinctive structure from ancient ritual and folk dances. It is essentially a poetic, quasi-religious, musical drama - without the dramatic conflict. Nō possesses inherently a remoteness from the reality of life, indirectness and abstract analogy, a composite of ancient myths and legends. Zeami Motokiyo (1363-1443) created the canonical framework of Nō out of contemporary but disparate customs, drawing on a precise knowledge of Japanese aesthetics, of long-established poetics and Buddhist teachings. The characters in Nō are closely linked to the concept of human nature, stemming from the religious principles of Zen Buddhism, representing mystical and spiritual perceptions.

Yukio Mishima (1925-1970) novelist, poet, dramatist, film director, army officer, is lauded as the first successful author of modern Nō plays. His intentions were to transform the centuries-old Japanese aesthetic form - which embody ambiguity, simplicity, vague language and deep-rooted Buddhist doctrine - into more of an intellectual and intelligible scheme, while still preserving the sensitivity and symbolism of the ancient form of Nō. He helped bring a stylistically 14th century art form into the 20th century.

Contrasting the old and new in his modern Nō, Mishima keeps the same titles and basic plots of the older plays, but uses contemporary speech, natural body language and stage settings. While in Zeami's Nō: feelings of passion are evoked in the observer, Mishima elicits intellectual response. While traditional Nō might stimulate a spiritual sense with overtones of lightness and life, Mishima generates anxiety with components of death.

As a result, these five plays have morphed into concrete versions of their abstract past selves, still representing the essence, the symbolic quality and suggestive elements of the originals* even in their crude modern settings; they are comprehensible and accessible to the otherwise ill-exposed Nō audience. Mishima's recreations stir-up excitement and tension, are metered in pace, tone, temper, and atmosphere. The narrative is tight, controlled, concentrated, not one word lies in waste.

The Plays:

Sotoba Komachi- set in a public park on a bench, a poet and a hag talk about the beauty she once was, and in so doing, he is 'bewitched' in viewing her as the archetypal woman who dominates the male psyche.

The Damask Drum- the old janitor of a building declares his love for a woman in the adjacent office, is given a message to beat the damask drum to win her love, only to be laughed at. In humiliation, he commits suicide. A supernatural design unfolds.

Kantan- a traveler naps on a magic pillow and dreams of a glorious life as Emperor of China. He awakens unable to distinguish dream from reality.

The Lady Aoi - a version of the tale of Genji love triangle takes place in a hospital setting. The gothic good vs evil is reminiscent of a Japanese horror flick - as a fan of such, this was my favorite!

Hanjo- about a teahouse geisha who exchanges fans with a gentleman as a promise of marriage, only to suffer madness by his abandonment of her. This story involves homosexual love and the only one that ends happily.

For the poorly diverse, opportunity-deprived but eager spectator of Japanese theater like myself, Mishima has provided coherent interpretation and exciting entertainment in these dramas, infusing his own flair for the dark and macabre, conjuring up a mysterious, mesmerizing, evocative, at times gothic world in which I enthusiastically enjoyed being immersed.

"Most encouraging of all, perhaps, is the fact that an outstanding young writer has devoted himself to this traditional dramatic art, and in so doing has created works of unusual and haunting beauty." - Donald Keene (translator)

*The original plays in old speech translated in English can be found here:

The Nō Plays of Japan by Arthur Waley (Grove Press, New York, 1953)

Anthology of Japanese Literature by Donald Keene (Grove Press, New York, 1955)

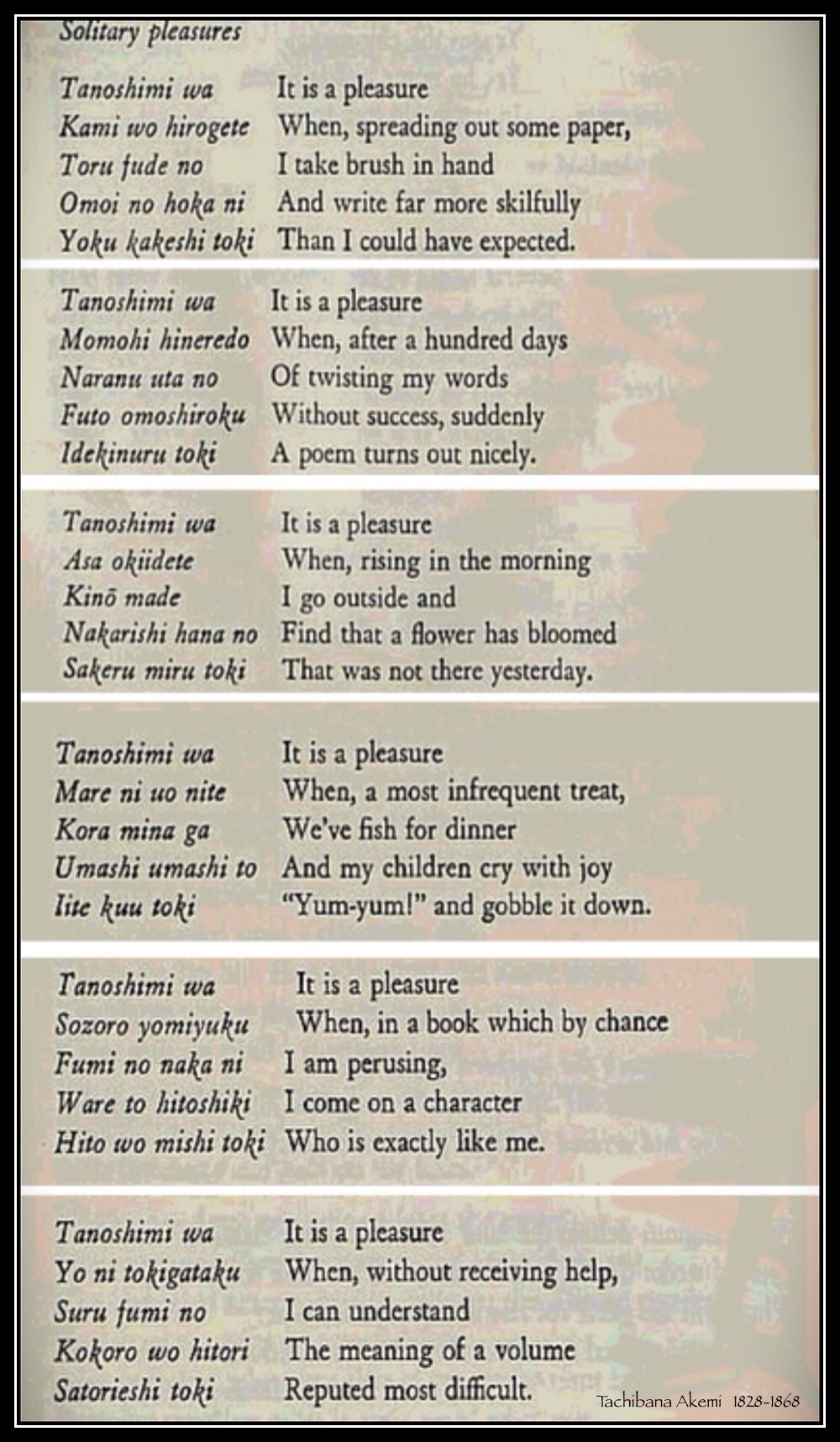

Solitary Pleasures by Tachibana Akemi

Excerpt from Anthology of Japanese Literature by Donald Keene

(Grove Press, New York, 1955)

The Good Women of China: Hidden Voices by Xinran

Back in Nanjing 1989-1997, Xinran ran a radio program called "Words of the Night Breeze," the motive in her words: "to open a window, a tiny hole, so that people could allow their spirits to cry out and breathe after the gunpowder- laden atmosphere"

[of the Cultural Revolution].

The Good Women of China: Hidden Voices is a compilation of 14 life stories taken from personal interviews of some of these 'survivors' - women whose lives were agonizingly destroyed, their families ripped to shreds, their existences pummeled into chaotic dust. For possibly the first time, these isolated women, of varying backgrounds and economic conditions, have been given a voice through Xinran. The stories are powerful, gripping, anguished accounts of inhumane treatment, torture, rape, hunger, death; all direct consequences of the Cultural Revolution.

Xinran's compassion for these women inspired her to recount her mother's story and that of her own destroyed childhood when, at age seven, she witnessed the Red Guards march into her home and burn all her family possessions, including cutting off her plaits and throwing them onto the fire: "From now on, you are forbidden to tie your hair back with ribbons. That is an imperialist hairstyle!" Her parents were imprisoned and she and her brother were made to suffer daily humiliations, labeled as 'polluters' of the revolution.

These stories, as overwhelmingly tragic as they are, are written in Xinran's exceptionally poetic prose, highlighting their deeply inspiring qualities, the unbreakable strength of maternal love and the everlasting endurance of the human spirit.

The Assassination of the Archduke

"Debris flew, windows shattered, and the crowd erupted in screams at the unexpected explosion," Sophie raised a hand to her neck where a splinter left its mark. Franz commanded the vehicle to stop, amidst the panic and mayhem in the streets, while spectators caught up with the assailant shouting, "I am a Serbian hero!" All was well again, they thought, and the motorcade proceeded to their destination. On the second lag of the motorcade's procession through the streets of Sarajevo, nineteen year old Gavrilo Princip readied his pistol.....eeny, meeny, miney, moe..., "where I aimed I do not know." Three shots. One pierced straight through Franz Ferdinand's plumed helmet, and as Sophie turned to him, registering the blood trickling down his mouth, she too contorted and slumped over. It was fourteen years to the day of their marriage, on June 28th, 1914 when the heir apparent to the Hapsburg throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Este and his wife, Sophie Duchess of Hohenberg were murdered in what was clearly a choreographed but badly executed series of attacks, considered to have been the catalyst that ignited the First World War.

The scar of culpability was branded into the Serbian government like original sin, guilty by its blatant disregard of constant rumors of a murder conspiracy and its inexcusable neglect in taking measures for high level security for the royals. Joint conspiracies across nations were suspected, trying to account for the incredible ease in which the government was blindsided by a young homicidal group of amateurs; even the Archduke had premonitions of his death prior to this very visit, but allowed his fears to be allayed by those he trusted. So utterly tragic too, was the accidental death of Sophie, who took a bullet meant for the Archduke - her death a regrettable mistake her assassin later confessed.

In this year of the 100th anniversary of the Sarajevo murders, biographers Greg King and Sue Woolmans have given a different view of Franz Ferdinand and Sophie Chotek, concentrating on their romance by painting a sympathetic story of a fairy-tale couple, who, against the disdain of imperial convention, were determined to be together in life and death - a tale that Princess Sophie von Hohenberg ( Franz's and Sophie's great granddaughter ) acknowledges has been long-awaited and a righteous, justified impression.

Historically, the Archduke's character and actions have been highly unpopular among many in both Vienna's and Budapest's circles. An aristocrat through and through, he was arrogant, militaristic, an openly vocal anti-Semite, harbored an unveiled hatred for the Magyars, and accused of political tyranny. What he personified was a prosperous but antiquated empire, a monarch-in-waiting whose politics and ideology were often contradictory, who held tightly to the reins of imperious power while his public feared he would become an extension of Emperor Franz Josef's iron rule, positioned obscurely between corruption and barbarism.

King and Woolmans focused on the personal side of Franz Ferdinand who suffered frail health since childhood, often plagued by 'bad lungs'. He was introverted, studious, isolated as a youngster and very much overshadowed by his siblings. He grew to be an attentive father and family man; married for love, a devoted husband and profoundly loyal to his 'dear Soph'. Sophie's tale is heartbreaking, and of the two, hers is the more captivating, human and realistic. Although born into nobility herself, her family was not considered an equal of the likes of the Imperial Hapsburg House, judged thusly as an inferior, incomprehensible ill-match for the archduke. Imperial decree demanded that, in order to marry Sophie: Franz Ferdinand had to swear that any offspring would irrevocably have no right to succession.

"... the consequences are that the marriage cannot be regarded as one between equals, and that the children springing from it can never be regarded as rightful children, entitled to the rights of members of Our House." - Emperor Franz Josef.

Almost daily since their morganatic marriage, Sophie was made to endure unspeakable humiliation, regarded with contempt and suffered constant, horrendous treatment by the imperial court. How she kept control of her self-respect through all that aristocrap is evidence of her indomitable fortitude and more than equal worth.

Their Cinderella story survived the most strenuously unnerving of imperial prejudices in an increasing politically unstable period for the empire, albeit to an unhappy ending one fateful midsummer's day, in the seminal event that triggered the most horrifying domino-effect of sequences, sadly leaving Franz's and Sophie's three children orphaned, to endure the condemned world their murder precipitated. Franz's prophetic and determined words declared years prior had finally come true: "even death will not part us!"

Part history, part romance: this biography was an illuminating view of the other side of Franz Ferdinand - although after reading more on the period that led to the tryrannicide, I'm not totally convinced that his character and politics were completely faultless. However, peering into the personal lives of the first fatal victims of WWI through King's and Woolmans's well-constructed scope was quite an intriguing and worthwhile learning experience.

Once A Jailbird by Hans Fallada

Once A Jailbird (1934) or Wer einmal aus dem Blechnapf frisst (The World Outside)

- He who once eats from the tin plate will eat from it again.

This grim novel is not merely about prison inmates and ex-convicts, but one using a social theme typical of Fallada, satirizing Hitler's New Germany with subtle criticism. It was published in 1934, just a year after the Nazi takeover, and so it's not surprising that Fallada might have subdued any political viewpoints.

Willi Kufalt, convicted of embezzlement and forgery, has served his time in prison and is released to work for his keep at a half way house set up by the new regime. After five long arduous years, he's happy to be free and vows that once the grim gray prison walls are behind him, he will never lay eyes upon them again.

But, the world outside that Willi had dreamed of is not what he encounters - his efforts to reform are hampered by the stigma of his prison record, and he is made to feel an outcast, not fit to associate with his fellow man. Resigning himself to this miserable fate, he begins to drink heavily and returns to the one thing he knows - the life of crime. He realizes he does not understand the world outside, and soon he's back in the environment in which he feels quite at home.

Fallada also drew on his own real life experiences in creating his sympathetic antihero, Willie Kufalt: notably the drinking, white collar crime, imprisonment, and estrangement from his family. The novelist's cynical perception of an unforgiving society is quite clear, and although written for specific German societal awareness, Once A Jailbird does have a modern and universal appeal. Some jailbirds of today may find an easier, cushier life being in prison than dealing with the outside world; to be honest, would a jailbird give up the roof over his head and the somewhat organized life he'd become accustomed to if he didn't have to?

How good it was to be back again. No more worries. Almost like home in the old days...It was better. Here a man could live in peace. The voices of the world were stilled. No making up your mind, no need for effort. Life proceeded duly and in order. He was utterly at home. And Willi Kufalt fell quietly asleep, with a peaceful smile on his lips.

Sweet dreams, Willi.

Mary Stuart by Stefan Zweig

No one could guess what the soul of a woman was capable of...

- Stefan Zweig: Mary Stuart (1935)

Aroused by the differing opinions on this controversial queen, Stefan Zweig sought to illuminate the view of the legend, not within the typical frame of researching a historical figure, but by psychological profiling of the protagonist, giving this biography the uniqueness of a dramatic thriller. He would interpret Mary Stuart as a strong-willed person but easily misdirected by her passion and idealized romantic values, who carved out her own destiny with flawed judgement to her ill-fated end.

A political pawn from birth, Mary Stuart was used to secure Scotland's and France's alliance. The same year Mary married the dauphin, Elizabeth succeeded Mary Tudor as queen of England. With issues still at hand over Elizabeth's illegitimacy, all the Catholic world thus viewed Mary Stuart the rightful claimant to the throne of England. This put Elizabeth politically on guard, making the most powerful woman in Europe a dangerous adversary of Mary's.

Mary Stuart widow of Francis II

Zweig perceived the recently widowed Mary's first impression on returning to Scotland like stepping backward 100 years, leaving behind a great civilization rich and luxurious: the sensual, refined and open-minded culture of France, in exchange for a narrow-minded one, ravaged and plundered for years, which kept no palace that could receive her with the dignity befitting her rank. From the moment Mary set foot to Scottish soil, she was made to battle her most formidable religious foe, John Knox, who defied the zealous Catholic Queen's rule over Church. Zweig believed Mary came "to realize that there were limits to her royal power," and, like a heroine from his novels, gave "way to her bitterness of soul in a passion of tears."

As the country emerged through Reformation and religious conflicts; rebellion and civil wars financed to undermine the throne of the Catholic Stuarts by none other than Queen Elizabeth, Mary's survival eventually came down to the war of the cousin-queens. A life or death struggle therefore took place between them and only death was able to settle the playing field. Zweig's analysis of the two monarchs uncovered the reasons why Mary lost that struggle.

Unlike her royal cousin, Mary rose to power and good fortune quickly, a queen already in the cradle, when hardly more than a child, she was anointed a second time anticipating a second throne; whereas Elizabeth fought illegitimacy and treason, barely keeping her own head from being axed while imprisoned, eventually succeeded the throne from the half-sister who first sought to annihilate her.

Not only did they differ in their rise as monarchs, but were equally different in feminine traits; their natures "were diametrically opposed." Mary was lighthearted, possessed a surplus of self-assurance, lacked seriousness of mind and lived for her own self-needs; her mind was stuffed with romance and she accepted her queenly position as a God-given right.

Nature had not only excluded Elizabeth from motherhood - well, not voluntarily as she purported - but perforce that she remained a "virgin queen." She could neither feel, nor think, nor act unambiguously or naturally and quite incapable of yielding to complete self-abandonment. Elizabeth lived for her country, was a realist, contemplating her position as ruler and looking upon it as a profession. While Mary gave in to primal basic feminine instincts, Elizabeth learned from her past to have dominion and reserve over hers.

Passion is needed in order that a woman may discover herself, in order that her character may expand to its true proportions; love and sorrow is needed for it to find its own magnitude.

Mary innately succumbed to impulsivity and the passion of love; to be swept off her feet and swallowed up in her desires. For the sake of one moment of passionate accomplishment, she risked kingdom, power and sovereign dignity, setting a trap for herself that was planted with the conception of her husband's murder. When Zweig examined Mary's feverishly penned letter of the night of Darnley's murder, he concluded it was significant evidence of her collusion, written by a guilt- ridden person, wrestling with her conscience.

We have a vision of black thoughts fluttering through the darkness like bats. Hatred flames up between the lines; compassion overwhelms it for a moment...it is not written alertly and clearly, but confusedly and stumblingly. It is not Mary's conscious mind that is speaking, so much as an inner self, the voice of trance and fatigue and fever- the subconsciousness with which it is so hard to get into touch, the realm of feeling that knows no shame. Very few documents have been preserved that revealed so admirably as this the hyperexcitability of one who is in the course of committing a crime.

He exposed her hand in Darnley's murder like a forensic investigator in a psychological-noir, surmising that her motives were directed by reckless passion and foolhardiness, manipulated by the will of bullish persons - the likes of Bothwell. It is with this same folly and the belief in her infallibility as a sovereign that she later married Bothwell, defended him, maintaining that she could not separate herself from him: "for if she did so, his child, which she bore in her womb, would be a bastard." Regarded by this time as lightminded, she continued to live in a 'cloud', a confirmed romanticist, unable to foresee her doom as an inevitable reality.

Conspiracy and intrigue up to the very last, Mary continued to ensnare herself in a net of her own making, while Cecil and Walsingham stood by to reel her in. Mary falls as a result of the impetuosity she imperially wore like a jeweled crown.

Queen Elizabeth I

As for Elizabeth's part, Zweig diagnosed her as bipolar, hysterical, excessively theatrical, double-faced in nature; believing unequivocally that she fabricated her ignorance of the death warrant.

One of the most remarkable capacities of persons of hysterical disposition is, not only their ability to be splendid liars, but to be imposed upon by their own falsehoods. For them the truth is what they want to be true, what they believe is what they wish to believe, so that their testimony may often be the most honorable of lies, and therefore the most dangerous.

Zweig prescribes that from a political standpoint, England was right in ridding the world of Mary Stuart. Morally, however, the execution was an unjustifiable action considered in a time of peace, but more especially from one monarch by another. Although Zweig concluded that Mary Stuart was culpable of criminal actions, having never learned to act with caution or forethought, he praised her nobleness of character and called her a morally superior individual, while he condemned Elizabeth as a dissembling, political murderess. In Zweig's eyes, Mary Stuart achieved victory over Elizabeth in a spiritual sense: martyred, dying a hero's death.

We all know the historical facts surrounding Mary Stuart, the most infamous of queens; and at this point, one more biography may not yield much difference than the next, especially one as dated as this. But seldom would we find a biographer such as Zweig whose flair for dramatizing psychological behavior in his characters brought freshness to a legend.

Commendable, readable, recommended.

Crown of Thistles: The Fatal Inheritance of Mary Queen of Scots by Linda Porter

Crown of Thistles: The Fatal Inheritance of Mary Queen of Scots may be more of a comparative-historical study of Scotland's and England's monarchs laid out side-by-side, than a fully mapped out biography of Mary Stewart, opening with sensational conquests and the supplanting of two kings: on one hand, by the victorious creator of the Tudor dynasty, Henry VII and the other, a 15 year-old boy who became James IV after revolting against his father.

Unlike many popular historians who have portrayed the histories of Scotland and England singularly, Porter draws striking comparisons between the rival territories- the two opposing Kingdoms in interminable contention - as Scotland prepared a siege on England, while England herself faced rebellion within her own border to the south-west.

Porter diligently shows the intertwined existences of these countries and their monarchal adversaries : their political conflicts, reformation, and familial relationships as they occurred alongside each other, as one country struggled for domination over the other.

Porter observantly notes Margaret Tudor's plight in seeing both her sons taken away from her much like her uncles Edward V and his brother Richard were lost to her maternal grandmother, Elizabeth Woodville. Margaret Tudor and her granddaughter Mary Stewart also presented uncanny similarities in their disagreeable positions with government; their choices of loves and dubious, unwise marital decisions (Margaret to the scoundrel Earl Angus, Mary to the murderous Darnley); their removed relationships with their own offspring; both their forced flights from Scotland into the protection of England.

Finally, the author insightfully suggests that Mary Queen of Scots's imprisonment by her cousin Queen Elizabeth I might have reminded her of "the unhappy precedent of James I of Scotland who had been a prisoner in England for 18 years at the start of the 15th century."

From Henry Tudor's first inception of a magnificent alliance, through tumultuous periods of hatred, backstabbing and bloodshed, Porter livens the histories of these two border rivals to their eventual melding into one great nation under King James VI and I.

I Served the King of England by Bohumil Hrabal

Man's body and spirit are indestructible...he is merely changed or metamorphized

- Bohumil Hrabal, I Served the King of England (1971).

Hrabal's satirically political, erotically imagined and poignant adventure story follows the rise and fall of a young busboy Ditie (Czech for 'child') who, being diminutive in stature, possesses big dreams and the determination to become a millionaire to be the equal of everyone else: is influenced by his father's advice to have an aim in life because then he'd have a reason for living, initiates his rise at the brothel 'Paradise'- a habit-forming place that, from Ditie's innocent viewpoint, is so wonderful and forbidden that I wanted nothing more in this world,... because at last I'd found a beautiful and noble aim.

His adventures surrealistically course through farcical scenes of life in wartime Prague, though he stumbles upward without much thought to moral implications, idealizing and fervently learning from the distinguished headwaiter who knows everything about everything because, as the latter puts it: "I served the King of England." Ditie's steps to elevated stature are vividly imagined, particularly in one ironic episode where he effortlessly fumbles into serving the Emperor of Ethiopia, Hailie Selassie: the similarity in their physical sizes is not lost on the reader.

I learned that feeling victorious makes you victorious, and that once you lose heart or let yourself be discouraged the feeling of defeat will stay with you for the rest of your life, and you'll never get back on your feet again, especially in your own country and your own surroundings, where you're considered a runt, an eternal busboy.

Hrabal depicts scenes of the German Occupation of Czechoslovakia through Ditie's relationship with Lise, a Nazi gym-instructor. Their marriage is expected to help perpetuate the future Aryan pure-blooded offspring of the Reich. Hrabal's highly erotic treatment depicting Germany in 'the throes of swallowing up' Czechoslovakia, of the latter forced to submission and, under pressure too, the ejaculation of its own identity proves this author's mastery of allegory. The handicapped nature of Ditie's and Lise's child is another ironic, powerfully piercing twist of the dagger in Hitler's ideology.

With Hrabal's signature taste for the absurd direction of Fate, his hero becomes the millionaire of his dreams but through the establishment of communism, loses that long sought-for stature, along with the freedom he thought it would afford him.

The final portions of Ditie's story are the most poignant, with a theme that the author often uses in his novels: memories, self reflection, and the expectations of one's life. Ditie becomes a road mender, and in his loneliness, he contemplates the direction he let his life take, coming to some profound conclusions of integrity and morality.

..the maintenance of this road was the maintenance of my own life, which now, when I looked back on it, seemed to have happened to someone else. My life at this point seemed like a novel, a book written by a stranger even though I alone had the key to it, I alone was a witness to it, even though my life too was constantly being overgrown by grass and weeds at either end. But as I used a grub hoe and a shovel on the road, I used memory to keep the road of my life open into the past, so I could take my thoughts backward to where I wanted to begin remembering...and so arriving, in this back and forth way, at the meaning of life. Not the meaning of what used to be or what happened a long time ago, but discovering the kind of road you'd opened up and had yet to open up, and whether there was still time to attain the serenity that would secure you against the desire to escape from your own solitude, from the most important questions that you ask yourself.

Hrabal's tragicomic tale of a nobody seeking to become important, and Czechoslovakia's pre-WWII to its Communism period may be one and the same. Ditie's introspective thoughts of his journey; of interrogating, accusing, and defending himself; and of finally moving forward, may be taken as reflective of Hrabal's beloved country. This highly inventive, equally erotic, funny, tragic, philosophical and inspiring work deeply touched and entertained. Just a word of caution, though..the movie was disappointing.

3

3

1

1