Nicole~

A man may try as hard as he likes but he'll never know what schemes a woman may be slowly and quietly carrying out behind his back.

The Tale of Enchi-

Fumiko Enchi started her career as a dramatist; she was influenced by Ibsen and Strindberg, and cultivated an interest in kabuki. She emerged in the early 50s as "a novelist of the fates of women both past and contemporary." Between 1967 and 1972 , she translated Murasaki Shikibu's The Tale of Genji into modern Japanese. It is with this most enduring Japanese literary classic that Masks draws its parallels, supping on the perception of a woman's possession of a hidden supernatural energy.

Masks is the story of vindictiveness, passion, jealousy and vengeance, of women in solidarity aiming to achieve retribution against men, to perpetrate "a crime only women could commit." It is an exploration of class, sexual oppression and the suppression of women in a traditionally patriarchal society. Enchi brilliantly weaves a reinterpretation of the character Rokujō lady from The Tale of Genji with the vengeful spirit of the heroine Mieko, whose husband Togano Masatsugu, "believed to be descended from a powerful clan in line to become feudal lords" and who still adhered to dominating, misogynistic codes, had caused her severe and immeasurable humiliation and suffering throughout their marriage.

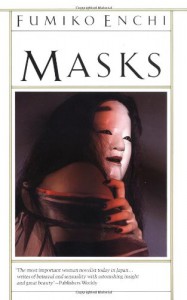

The novel is sectioned into three chapters, each named for Nō masks which metaphorically depict the novel's "cloaked" particulars, and in turn define its supernatural concerns.

The first chapter named Ryō no onna means 'spirit woman', the vengeful spirit of an older woman tormented by the bitterness of her life. Mieko's obsession with 'shamanism', spirit possession, and artful yet subtle manipulation become evident here. In her scholarly treatise relating to The Tale of Genji, Mieko seems to sympathize and identify with the character Rokujō lady. She writes : "As passion transforms the Rokujō lady into a living ghost, her spirit taking leave of her body again and again to attack and finally to kill Genji's wife Aoi, the commentators see in her tragic obsession a classic illustration of the evil karma attached to all womankind...the Rokujō lady turned unconsciously to spirit possession as the only available outlet for her strong will. The Rokujō lady is instead a Ryō no onna: one who chafes at her inability to sublimate her strong ego in deference to any man, but who can carry out her will by forcing it upon others and that indirectly, through the possessive capacity of her spirit."

The second section of the novel is named for the Nō mask Masugami meaning "young madwoman," a woman as victim, a young woman in a state of frenzy . Each female character had at some point been reduced to a frenzied state: Aguri -the mistress, Mieko -the wife, Yasuko- the daughter in law, Harumé -the mentally handicapped daughter. Through Yasuko, Mieko controls the seduction of Ibuki (Yasuko's lover). He awakens to find Harumé in his bed; the treachery that he experiences is veiled in a dreamlike scenario. "Her heavily rouged, camellia-bright lips were ripe with sensuality, and her face was the face of Masugami - The mask of the young madwoman which he had seen at the home of Yorikata Yakushiji. It was all wrong...not knowing whether he might be drunk or dreaming, but sensing with faint vestiges of consciousness that rational thought lay for the time beyond his powers."

A woman's love is quick to turn into a passion for revenge - an obsession that becomes an endless river of blood flowing on from generation to generation.

Fukai heads the third and final chapter, meaning "deep well or deep woman", depicting middle-aged women, a metaphor comparing "the heart of an older woman to the depths of a bottomless well-a well so deep that its water would seem totally without color." Mieko finally defines herself in this mask. After the twist and anguish that comes full circle like karmic influence, Mieko is left bereft. She comes to understand the crime she has perpetrated, realizes the result of her revenge and its effect on herself and others. The final scene is so esoteric- the reader is mesmerized by Mieko's hypnotic kabuki -like pose: "In that moment, the mask dropped from her grasp as if struck down by an invisible hand. In a trance she reached out and covered the face on the mask with her hand, while her right arm, as if suddenly paralyzed, hung frozen, immobile, in space."

For those who have read The Tale of Genji, Masks is a welcomed, very brief revisitation of the Murasaki classic. The supernaturalism is rendered in typical Japanese style- subtle, mysterious, illusory, poetic; it will utterly engage fans of Japanese fiction writers like Tanizaki and Kawabata.

5

5